What we can learn from The Guardian's membership strategy

It reached 1 million recurring paid members without implementing a paywall.

Welcome! I'm Simon Owens and this is my media newsletter. You can subscribe by clicking on this handy little button:

Let’s jump into it…

What we can learn from The Guardian's membership strategy

Turnaround stories are rare in the media industry, especially for legacy print outlets that were caught flat footed by the internet era.

Take Newsweek as an example. At its height, it was arguably the most influential magazine in the country, read by tens of millions of Americans each week. But by 2008, it was hemorrhaging cash. After a series of acquisitions, it ended up in the hands of a spammy media company, the owners of which eventually pleaded guilty for fraud. Nobody today affords the magazine with the same respect it commanded 20 years ago.

While Newsweek is somewhat of an outlier in terms of reputation loss, it’s far from the only publication to suffer a precipitous decline. Chances are that your own local metro daily is a shell of its former self, decimated by falling ad rates and multiple rounds of layoffs.

That’s why media turnaround stories are so fascinating. The New York Times is the perfect example. It was only a little over a decade ago that it was forced into accepting an emergency cash infusion from Carlos Slim. Pundits at the time were writing earnest columns wondering whether the Grey Lady would still exist within a few years. Then in 2011 it launched its famed metered paywall, and the rest is history. Now, pundits openly wonder whether the Times has become a monopoly, bleeding all its competitors dry of their star talent.

The Guardian represents another remarkable turnaround, and it’s somewhat unique in how it accomplished it. As recently as 2016, it was deep in the red — losing around $89 million a year — with its main benefactor projected to run out of money within the decade. While the 200-year-old newspaper had made substantial audience gains and even won a Pulitzer in 2014, that success wasn’t translating into more revenue.

But by the end of 2017, The Guardian’s outlook was entirely different. An effort to jumpstart its reader revenue operations had borne fruit, and it had grown from 12,000 paying members the previous year to over 300,000. By 2019, it broke even, and in 2021 it announced it had reached 1 million members. Earlier this month, the newspaper reported that it “has recorded its strongest financial results since 2008” and that “annual revenues at Guardian Media Group grew by 13% to £255.8m.” This resulted in a cash surplus of £6.7 million.

All that would be remarkable on its own, but what makes The Guardian’s turnaround especially notable was that it accomplished this feat without implementing a paywall.

How did it do this? And what can other publishers learn from this success? Let’s dive into some of the factors at play:

Its quasi non-profit status

The Guardian isn’t your standard corporate media company. Since 1936, it’s been overseen by the Scott Trust, a $1.3 billion investment fund that exists to ensure the newspaper’s independence. While I don’t know if this technically makes The Guardian a nonprofit under UK law, it certainly gives the outlet the kind of leeway needed to present itself as a public good.

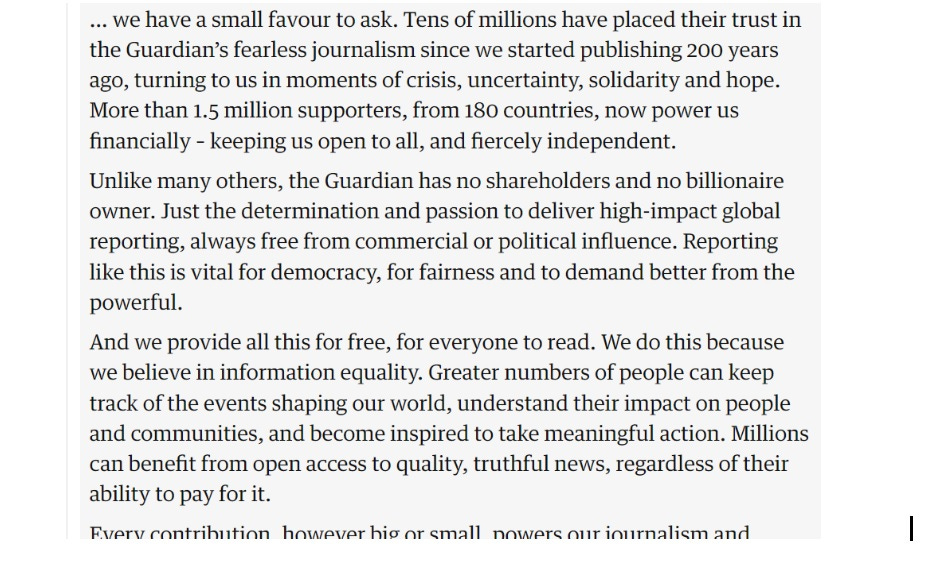

You can see this framing in its calls to action messaging at the bottom of its articles: "Unlike many others, the Guardian has no shareholders and no billionaire owner. Just the determination and passion to deliver high-impact global reporting, always free from commercial or political influence." This is the type of messaging you see from a public radio or PBS pledge drive, and it makes it easier for readers to stomach the idea of turning over their credit card information despite a lack of paywalled content.

Some for-profit media companies have tried this strategy, with mixed results. Both Vox Media and BuzzFeed try to solicit donations within their articles and newsletters, but in all the interviews with their executives that I’ve read, I’ve never seen donations cited as a significant driver of revenue. Audiences just don’t feel compelled to give money to VC-funded entities.

A running “articles read” meter

I thought this was particularly clever: in its call to action to donate, The Guardian informs you of how many articles you’ve consumed:

I have a Washington Post subscription but I honestly couldn’t tell how many WashPo articles I read a month, on average. I think most people do a bad job of estimating how much media they consume. The Guardian’s article meter serves as a gentle, prodding reminder that the reader actually is receiving value from the outlet. I can imagine that the higher the meter gets, the more obligated the person feels to finally take out their wallet and donate.

Mission-driven guilt messaging

If you want to get readers to pay in the absence of a paywall, then you need to convince them of the importance of keeping your journalism free to access. Take a look at the messaging that appears at the bottom of Guardian articles:

But it’s not just through messaging that The Guardian appeals to donors. It also eschews the American-style journalism that strives for both-sides, view-from-nowhere coverage, and instead it leans into more progressive values. The strategy, coupled with its decision to invest heavily in its American newsroom, has resulted in strong donor growth outside the UK. This approach was especially fruitful during the Trump years. Per Digiday:

Guardian US has benefited from the Trump bump that’s driven readership and subscriptions for The New York Times, The New Yorker and others. But while that support has leveled off elsewhere, reader support for Guardian US has continued, as the publisher has launched editorial series on the threat to public lands, environmental threats and other subjects it considers to be undercovered, to test people’s willingness to support specific coverage areas.

As a result of this strategy, over half of its donations come from US readers, and it’s now doubling down on covering progressive issues like the environment and climate change.

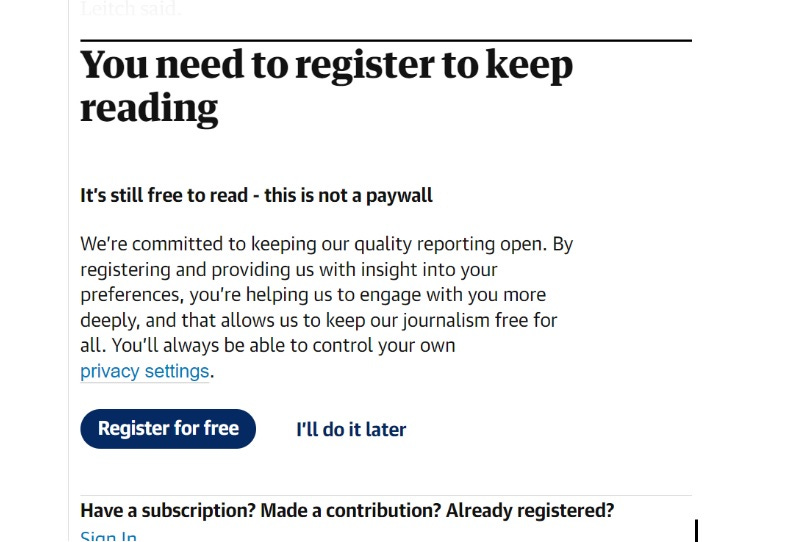

Its soft registration wall

News consumers have grown more savvy; they know how to sidestep metered paywalls by opening articles in Incognito Mode or utilizing a different device. At the same time, publishers have grown more focused on leveraging first party data when targeting their ads.

That’s why many outlets have launched registration walls that require users to create an account before they can access free content. This makes it more difficult for readers to avoid paywalls, forces casual readers to turn over their email address, and allows the publisher to better track their interests.

But the registration wall also creates a pretty bad user experience. Typically, the reader has to come up with a new login and password, then go to their inbox to confirm their registration. That’s a lot to ask of a first-time visitor who just wants to read a single article. Whenever I hit a registration wall, I often just close the browser tab and move on. It’s not worth the hassle.

What I like about The Guardian’s registration wall is that it’s a little more user friendly:

See that “I’ll do it later” button? That basically closes the registration window and allows you to consume the article unhindered. It probably results in fewer account registrations, but also likely drives down the number of people who simply bounce off the page.

But why does The Guardian need a registration wall when it doesn’t have a metered paywall? Well, as I mentioned, it allows the newspaper to collect first party data that it can leverage in its ad targeting, but a registration also opts readers into The Guardian’s newsletter. As just about every publisher case study has shown, newsletter subscribers form daily habits and convert to paid at a much higher rate than casual visitors.

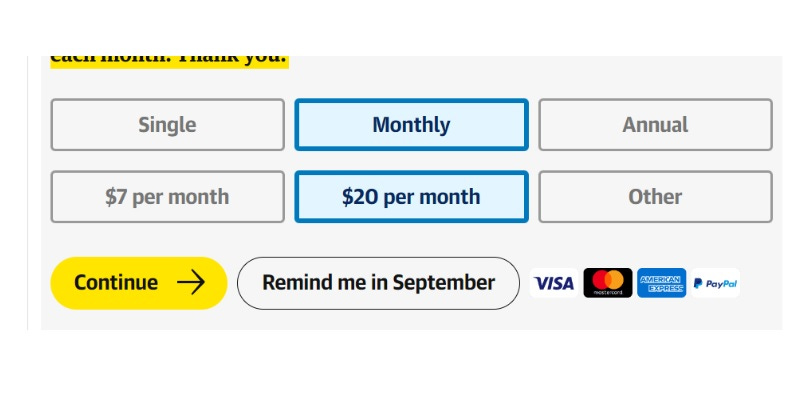

Allowing for both subscriptions and single donations

Every subscription model faces the same conundrum: up to 80% of online media consumers say they will never, ever pay for a digital news subscription. It doesn’t matter how many ways you optimize your paywall or roll out new content categories; these people are unmovable.

Some within the media industry see those statistics and claim that micropayments are the answer, but I’ve written before about why micropayments won’t work for most. If you run a subscription paywall, it’s very difficult to repackage your content in such a way that allows for one-off payments at scale.

But the beauty of The Guardian’s lack of a paywall is that it has more flexibility in how it solicits donations. Here are the options it presents:

Not only do one-off donations drive a significant portion of The Guardian’s reader revenue, but these donations also place the reader in its newsletter funnel, allowing the publisher to focus on converting one-off donors into recurring members.

Unhindered advertising inventory

Most publisher CFOs won’t publicly admit this, but there’s a downside to subscription models: they hinder advertising growth. If you’re locking down content behind a paywall, then you’re limiting advertising reach and inventory. I’ve listened to interviews with publishers who claimed otherwise, but they’re all lying.

The Guardian’s lack of paywall has allowed it to have its cake and eat it too. It was able to benefit from the post-pandemic boost in advertising revenue while simultaneously continuing to grow its paid membership.

Cost cutting

I’d be remiss if I didn’t at least acknowledge that The Guardian’s leadership team made significant efforts to reduce costs in 2016, partly by eliminating 400 positions. While job cuts are never ideal, it likely provided the newspaper the opportunity to restructure its operations and move away from a print mentality. Other than a pandemic-induced round of layoffs in July 2020, it seems to have avoided severe cost-cutting measures for the past six years.

***

There you have it. Given The Guardian’s somewhat-unique status as a non-corporate media outlet, I don’t think every publisher could copy its strategy wholesale, but there’s a lot to learn here about how it created a better user experience, offered more options to its readers, and sharpened its editorial mission. The Guardian put its readers first and then found great ways to generate revenue by engendering good will from those readers. More publishers should follow suit.

Get smarter about all things digital. Start and grow your first online business

[Sponsored]

Want a deep dive into further levels of affiliate marketing, SEO, ecommerce, digital analytics, etc.? Want to learn from a group of people building digital businesses?

There are a few trends that aren’t going away.

Remote work is here to stay. This frees up an enormous amount of time. You now have a choice of how you spend that time.

Outsourcing is coming more and more. If you can do your job from your bedroom, someone on the other side of the world can do your job for 1/4 of the price. There’s very few of you that are actually immune. You’re probably not the exception.

Automation is here to stay. If your job isn’t outsourced, management is going to try to automate your job. Over the next 10-15 years, you’re going to be surprised at the number of jobs that will be automated.

So, what’s the solution?

Work for yourself. Learn & scale affiliate marketing, ecommerce, SaaS, or an online service business.

Control your own destiny.

Quick hits

Keith Olbermann is a fascinating media figure in that he's a great broadcaster but doesn't work well with corporate bosses. I always thought he would have made a great indie podcaster or YouTuber if he'd been born 20 years later. [WSJ]

"New data from OpenWeb’s network of 1,000+ global publishers shows that those who engage [comment on articles] view 4.5X more pages. They also spend 3.6X more time on-site, and drive 3.2X more revenue than non-engaged users. Better yet, on average, 25% of these users return monthly." [OpenWeb] This is why I’m super responsive to comments and also have been running my regular Q&A series in my newsletter.

I was interviewed on a podcast! For this one, I went deep on my career transitions back and forth from journalism and marketing and then finally running my own media operation. [Video Husky]

“Barstool became Barstool when Deadspin stopped being Barstool.” [The Guardian]

Comics are booming right now, but not the kind you might think. [NYT] From the article: "Webtoon said its top Korean creators can make in the range of $250,000 a year."

lol. Newsweek is launching a digital subscription product. So many publishers think they can just slap a paywall onto a website and the money will flood in, even when they've tarnished the outlet's brand with low quality content. [Axios]

Let’s make it personal

Want to chat with me directly? I maintain a private Facebook group and basically hang out it in all day chatting about media industry news, and it’s full of lots of successful media operators who often chime in with their own expertise. The quality of the discussion is super high because I only promote it at the bottom of this newsletter. You can join here: [Facebook]

Do you like this newsletter?

Then you should subscribe here:

Simon Owens is a tech and media journalist living in Washington, DC. Follow him on Twitter, Facebook, or LinkedIn. Email him at simonowens@gmail.com. For a full bio, go here.

They also offer a special feature in their app for members only, so it's not just a donation, there is some value add there.

Nicely done...