How a former Cosmo editor built Australia's largest women-focused media company

Mia Freedman started Mamamia as a one-person blog and bootstrapped it into a multi-media outlet that reaches 7 million people.

Welcome! I'm Simon Owens and this is my media newsletter. You can subscribe by clicking on this handy little button:

Mia Freedman had the kind of magazine career that most journalists can only dream of.

She was hired as an intern at Cleo at the age of 19 and quickly worked her way up to feature writing. Then, after bouncing around as a freelancer, Freedman accepted the role as editor-in-chief of Cosmopolitan’s Australia edition. She was only 24 years old. “That made me the youngest editor of Cosmo's 65 international editions,” she told me in an interview. “I was the editor-in-chief of Cosmo for seven years and took it to number one in the Australian market.”

Despite achieving the kind of success that most journalists don’t see until they’re in their 40s, Freedman grew frustrated by her corporate bosses’ refusal to embrace the then-burgeoning web. “I really struggled with trying to convince them that we had to move our brands to digital,” she said. “They saw themselves very much as a magazine company and a print company, not a company of brands.” Rather than getting its own website, Cosmo’s content was licensed out to one of the major web portals that dominated the internet in the late 90s and early 2000s. “They really saw the websites as only a way to try to get people to buy more magazines. It ultimately led to the demise of all those women's magazine brands that I used to work on.”

After Freedman left Cosmo, she did a brief stint in TV that involved launching a daytime women’s talk show. It was a job that she later described as “god awful” and full of “big swinging dicks,” and it seemed obvious to her that the male executives she worked with didn’t understand women at all. So during her free time she began to sketch out an idea for a website that would cater to women, but not in a patronizing way. “At that time, the only women's websites in Australia were niche,” she explained “So there were parenting sites, beauty and fashion sites, gossip sites, and cooking sites. And every woman I knew was interested in all those things, but also 10 other things like news, current affairs, and pop culture.”

One day in 2007, Freedman put some of her ideas to paper. As she explained later in an essay, “I sat down at my kitchen bench, cut some letters out of a magazine to spell ‘Mamamia’ and sent it to a friend of a friend who was a website designer.” By this point, the internet had firmly entered the Web 2.0 era, and blogs were proliferating. When Freedman was editor of Cosmo, a would-be internet publisher needed to build a website from scratch, but now there were any number of blogging platforms that could be launched in a matter of minutes.

At work, she was growing more miserable by the day, and she knew she wouldn’t last much longer. The only question that remained was whether she would leave on her own terms. It didn’t take long for her to make a decision. As she wrote later in that essay, “I took those magazine cutouts, registered the URL Mamamia.com.au, negotiated a redundancy, and created Mamamia.”

At first, Mamamia was just a one-person blog, a project she ran from a laptop in her lounge room. But then it quickly found an audience, with each post spawning sometimes thousands of comments. Over the span of the next decade, Freedman brought on her husband to help run the business, hired dozens of employees, and launched a thriving podcast network.

Today, Mamamia is not only one of the most successful independent media businesses in Australia, but it operates the largest women-focused podcast network in the world. It monetizes through multiple revenue streams that include branded content, ecommerce, and paid subscriptions. And it did all this without taking on VC investment.

How? In an interview last July, Freedman and her husband Jason Lavigne walked me through how they built the business, why they avoided programmatic advertising, and what compelled them to launch a podcast network when most other publishers were focused on video. Let’s jump into my findings…

A humble blog

Visit the Mamamia headquarters today, and you’ll find a sprawling network of editors, journalists, and other media specialists, but in the early days it was just Freedman on her laptop. “I was writing about six articles a day, trying to do some basic coding, and moderating all the comments,” she said. “This was before social media, and there would be up to 2,000 comments on a post, sometimes.”

Obviously with that level of output Freedman didn’t have the time to conduct any original reporting; instead, her posts were a mixture of aggregation and commentary. “People started to take notice because I had an already-existing profile. I was writing a weekly newspaper column that was national, and I had a profile from my previous work in magazines.”

She also had very little competition. Over in the U.S., there was already a thriving feminist blogosphere, but the equivalent didn’t really exist in Australia. Within only six months or so after launching Mamamia, Freedman realized she had a vibrant community on her hands. “One of the most popular posts I did was a column about the best and worst moments of my week. And then there would be sometimes 2,000, 3000 comments of women sharing the best and worst moments of their week and talking to each other. There was nothing like Mamamia in the Australian market, which is why we had such a first-mover advantage.”

From the very beginning, Freedman knew that Mamamia could one day be a business, but she had neither the bandwidth nor the expertise to figure out how to make that transition. “It was just me. I had two young kids at home, and then I fell pregnant with my third.” This was well before the current Creator Economy era, so she couldn’t simply launch a Substack newsletter and start charging for subscriptions. Even the digital advertising market was much smaller back then.

Luckily for Freedman, her husband Jason Lavigne had just the sort of business background needed to take Mamamia to the next level.

In 1999, Lavigne founded what became one of the largest wine and beverage suppliers in Australia, and in 2007 he sold it to an organization called The Wine Society. “The global financial crisis hit here in Australia at the end of 2007, early 2008, and I was looking around for what I was going to do next.” He told me that, coincidentally, he started to invest in various digital media businesses, most of which hadn’t yet launched.

And then, lo and behold, his wife launched a media outlet that had the kind of off-the-charts organic engagement that most news startups could only dream of. The timing couldn’t have been more perfect. “I was flying over to Boston to do an executive education course at Harvard Business School,” he said. “But the problem was that I didn't actually have a specific business at the time. Not only was I missing the cut and thrust of running a company day to day, but I also had nothing to plug into this course. So by the second year, everything culminated to this point of Mia and I having a discussion where I said, ‘look, why don't I come in and see if we can commercialize and monetize this and make a business of it.’ We decided that if we couldn’t do it in a year, then it was probably time to move on and get a salaried job so we could pay our mortgage.”

And that’s how Lavigne ended up coming on as CEO of Mamamia in 2009. He immediately set out to find a way to monetize the site’s extremely engaged audience.

Building a business

Lavigne went into his role with a completely different mindset than Freedman. Whereas she viewed Mamamia as a blog that rested largely on her personal brand, he knew it needed to be something much bigger than that. “I thought maybe a big media company would come and buy it and Jason pointed out that there was nothing to acquire. It was just me and my laptop. That's when he started to challenge me about what Mamamia could be. In many ways, he had the vision before I did.”

It didn’t take long for Lavigne to settle on Mamamia’s initial business model: advertising. But he knew that the site didn’t have the level of massive scale needed to truly succeed with standard display ad units. “You couldn't commercialize that traffic meaningfully on networked CPMs, so we had to find another model that would work,” he said. “And the model I chose to plug in was branded content, or what’s otherwise known as native advertising.” Lavigne wanted to position the site as a “premium” brand, not one that simply sold bottom-of-the-barrel programmatic advertising.

This model wasn’t completely alien to Freedman. After all, she’d come from the world of women’s magazines, which regularly published advertorials. Lavigne developed relationships with Australian media buying agencies, and whenever he landed a new client, he’d turn the creative brief over to Freedman to actually write the sponsored blog post. “We were probably selling five sponsored posts a month, or thereabouts, in the early days,” said Freedman.

Lavigne’s gut instinct was correct. Within the first year after he came on, Mamamia was generating a whopping seven figures in revenue. They were getting so much advertiser demand that they began to grow worried that the ratio of editorial content to paid posts would start alienating readers, so they decided they needed to bring on writers to create more non-advertising articles.

At first, they hired what Lavigne referred to as “generalists” – people who could write and edit articles on a wide range of topics. “We've never taken investment,” he said. “We were bootstrapping, and we didn’t have an open checkbook in terms of hiring people. So we started off with generalists and slowly moved towards specialists.” Hiring sometimes proved hard since they were competing with legacy media. “Most people hadn't jumped from magazines yet, so it was almost impossible for me to lure people, because they were getting paid enormous amounts of money,” Freedman said. “And my pitch to some of my former colleagues was like, ‘come and work longer hours for less money than you do right now.’ And they were like, ‘great idea. That sounds very appealing.’”

Freedman worried there would be an audience backlash to the new bylines. After all, the blog’s entire foundation was built on her own personal brand. But the transition ended up going pretty seamlessly, and she was able to step back from day-to-day content creation and begin to think about a bigger picture editorial strategy.

In its first few years, Mamamia received most of its traffic from platforms like Google and Twitter, but of course that all changed in the early 2010s when Facebook turned on the traffic spigot and started heavily featuring media outlets in its Newsfeed. Virtually overnight, Mamamia’s traffic exploded, and it quickly became one of the most-visited news sites in Australia. “I think the experience of working in magazines for 15 years and writing headlines became really helpful in the age of social media,” said Freedman. “A tweet was around the length of a headline, and I'd spent my whole career learning from some of the best people in the world on how to write really engaging headlines and cover lines. So that meant that we were able to have an outsized presence compared to other much bigger media brands on those social platforms, and this was years before they even really focused their attention on what an important source of audience those platforms were.”

Suddenly, Freedman was no longer just a blogger and former magazine editor; she was a media mogul, the equivalent maybe of an Australian Arianna Huffington or Jonah Peretti. Mamamia was quoted in Parliament, and it started to accrue mainstream recognition for its left-of-center feminist voice. I asked Freedman if the site broke any major stories. “We do a lot more original reporting now, but back then it was much more opinion and voices.” Often times she and her fellow editors found themselves discussing what the Mamamia viewpoint was on a particular issue. “We've never confused ourselves with The New York Times.”

Diversifying the business

The first decade of Mamamia’s existence was a period of rapid expansion. After spending two years running the site out of their house’s lounge, Lavigne and Freedman rented their first office. “We started hiring people, and very quickly those offices filled up,” said Lavigne. “We had 15 people, then 30 people, and then we sort of burst out of that office. We've now got around 100 staff.”

As the company grew, it started launching new verticals and business models. It debuted the Social Squad, which describes itself as a “full service content and influencer agency.” It’s since been contracted by dozens of national and international brands to execute on marketing campaigns in Australia. Mamamia also built an online courses business called Lady Startup. “It's a six-week online course that's taught by me,” said Freedman. “We've got two courses, one for launching a business and one for those who have already launched a business and want to grow it. It came from so many women coming up to me and saying that they wanted to start businesses, whether it was small businesses or side hustles, but they just didn't know how. And so we decided to use our knowledge of running a business for over 14 years to help and support other women.” The courses cost $597, and, according to the website, it’s sold to “over 5,000 Lady Startups and counting.”

Of course, not every experiment was a home run. When conducting research about Mamamia, I came across old articles about various initiatives that included a national radio program, a health and beauty mobile platform called Glow, and even a US-based news site called Flo & Frank. Many of these verticals ended up being folded back into the Mamamia brand or closed entirely.

But the thing about these kind of experiments is you really only need one or two of them to pay off in a big way, and that’s what happened in 2016 when Freedman decided to launch a podcast.

Building the largest women’s podcast network

Podcasts were invented all the way back in 2005, but it was only recently that the industry started generating real revenue. In the U.S., it didn’t even cross the $1 billion threshold until 2021, and Australia was even further behind in terms of growing a sustainable podcast ecosystem.

The reason I’m telling you all of this is to illustrate how much Freedman was going out on a limb by devoting any of her energy to podcasting in 2016. “No one was really doing podcasts here and I couldn't even wrestle up that much enthusiasm inside the company,” she said. The first podcast the company launched was called Mamamia Out Loud. “It was me and someone else that I grabbed from the office, and we were sitting on the floor with an iPhone, talking into it about what women were discussing that week.”

To call it a business back then would have been a stretch, but the podcast did benefit from having virtually no competition. “We had a first-mover advantage because, even internationally, nobody was there,” said Freedman. “Slate was doing podcasts, but other than that, there were no big media companies, or even the small ones, doing podcasts. They just didn't have their eye on that prize.” This was the era, remember, when publishers were burning through vast sums of money to build up their Facebook video operations. “While every other media company was pivoting to video, we actually pivoted to audio. We pivoted to podcasts.”

Lavigne estimated it probably took two years or so before his team was able to start monetizing the podcasts. “We originally had to throw in some ads for free so brands could test them out, and then suddenly they started coming back and telling us that the podcast ads were the most effective parts of the campaign.” In the U.S., most podcasters were still selling direct response advertising — the kind that included a discount code to the brand could track sales — but Mamamia had virtually no trouble selling to the more coveted brand advertisers, the kind who had massive marketing campaigns that were aimed at elevating general brand awareness.

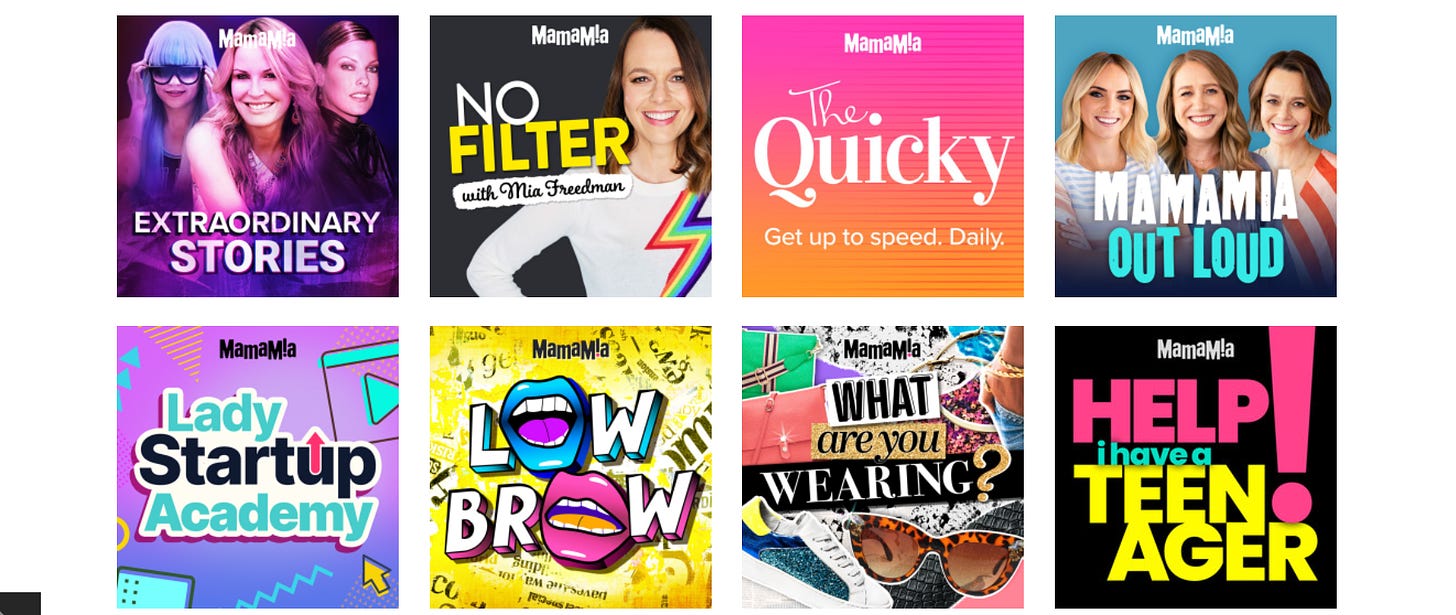

Once the revenue model was in place, Mamamia’s podcast slate exploded, eventually expanding to over 40 shows. While many of these podcasts follow the low-cost discussion format in which multiple personalities chat with each other — think Joe Rogan or Fresh Air with Terry Gross — the company also developed some more costly, highly-produced narrative shows. When conducting research for this article, I started clicking through Mamamia’s podcast catalog and sampled several episodes. Here’s a random selection:

No Filter: This is an interview podcast hosted by Freedman. In the episode I listened to, she spoke to one of the contestants from “Married, At First Sight” about what it’s like to star on a reality TV show.

Extraordinary Stories: This is a narrative nonfiction podcast about “the truth and tragedy of some of the world’s most remarkable women.” I sampled from a three-part series about the Pam & Tommy sex tape scandal, and it clearly benefited from good sound design, original interviews, and a narrative arc.

Lowbrow: This is a conversational show about pop culture. The one I listened to was about Angelina Jolene marrying Billy Bob Thorton in the 90s.

Though advertising funded the expansion, the Mamamia podcast network has since sprouted multiple business models. Like Slate, it now publishes bonus content behind a subscription paywall. It also launched live podcast tours, a line of business that wound down during the pandemic but has since sprouted back up over the last year or so. “That was another dual source of revenue that included ticket sales and event sponsorships,” said Freedman.

So an audio experiment recorded on Freedman’s iPhone eventually evolved into one of the biggest parts of the business. When I spoke to the couple in 2021, they were projecting that podcasting would eventually account for a majority of Mamamia’s income. “In terms of revenue last year, the podcast network contributed about a third,” said Lavigne. “This year it will be approaching closer to half. We think that next year it will be the same size as our overall business.”

Today, Mamamia is not only Australia’s largest women-focused news outlet; it’s arguably the largest independent media company in the country. What started as a one-person blog has bootstrapped its way to a household name, and Freedman is a veritable media mogul. Not all of its experiments worked out, but its singular focus on serving its core audience helped cement its stature as one of the most innovative digital media outlets to emerge this century. It’s an accomplishment that even Rupert Murdoch himself — who launched his global media empire with a single Australian newspaper — would find impressive.

Do you like this newsletter?

Then you should subscribe here:

Simon Owens is a tech and media journalist living in Washington, DC. Follow him on Twitter, Facebook, or LinkedIn. Email him at simonowens@gmail.com. For a full bio, go here.

Such an inspiring read

Great interview and coverage. Great to see that early headline/ransom note cut-up aesthetic continue into podcasts and other channels.