Welcome! I'm Simon Owens and this is my tech and media newsletter. You can subscribe by clicking on this handy little button:

Can publishers stop their journalists from launching Substack newsletters?

Back in 2006, when I was working my first job as a reporter at a Virginia weekly newspaper, I received an ominous request from my bosses: they wanted me to drive the half hour to headquarters for a meeting. I can’t remember if they lied about what the meeting was about or simply didn’t tell me, but I know 22-year-old Simon was completely blindsided when they revealed, behind closed doors, why I had really been called in: “We know you’re blogging during work hours.”

I don’t think they ever directly threatened to fire me, but the threat was implicit. I left that meeting with the clear understanding that I should never publish a post during normal work hours again. At my next newspaper job I decided not to even inform my employers I had a blog, a scenario that became increasingly awkward when the blog attracted some mainstream media attention and I had to duck out of the office to field radio interviews. It wasn’t until after I left the newspaper that I found out my bosses knew about my blog the entire time; they just never decided on what to do about it.

Over the next few years, journalists occasionally got fired upon the discovery they were blogging on their own sites. Chez Pazienza, a longtime TV producer, famously decided to not sign an NDA when CNN fired him for blogging, and he then used that same blog to burn every bridge he had at the network. The move exiled him from the insular TV journalism world, and he spent the next several years struggling to gain employment.

With the rise of social media, it became increasingly difficult for publishers to insist that their reporters couldn’t maintain an online presence. By 2012 or so, they were grudgingly acknowledging that an employee with a large social media following could actually aid in driving traffic to a media outlet’s content. That’s not to say they ever grew completely comfortable with this dynamic. Most rolled out vague social media policies that are still regularly used to fire journalists til this day.

Why am I recounting this history now? Well, a few weeks ago I wrote about the trend of freelance journalists leveraging platforms like Substack to produce supplemental income. Under this dynamic, the freelancer uses Substack as a “home base” to promote their writing and then utilizes its paid subscription feature to help round out their monthly freelance income.

Well, it turns out that it’s not just freelancers who have embraced Substack; several salaried journalists are launching newsletters, and, according to Digiday, many media executives don’t know whether they like this trend:

These kinds of newsletters ... fit into a professional gray area. Most media companies prohibit their reporters from doing freelance work that could be seen as competitive with their day jobs, and managers in any talent-focused industry have always worried about the talent building an audience their employer doesn’t control and can’t monetize.

It’s hard to see how the publishers have any real standing to block their reporters from launching newsletters. As Steve O’Hear, a reporter at TechCrunch, put it to Digiday, “It’s like telling a reporter they can’t have a Twitter account.” Indeed, what’s the material difference between what can be posted to Facebook vs what you’d write in a newsletter? If anything, Facebook is a much more direct competitor to the publisher, seeing as how it’s vacuuming up an increasingly larger portion of online ad revenue.

I could see how an employer would make the argument that you can’t launch a paid version of a Substack newsletter without permission. Most media outlets have policies in place requiring employees to ask permission before freelancing for competing outlets, and if you squint at it the right way, running a paid newsletter is similar to freelancing.

I’ll end this piece with another anecdote: Last year a major media company offered me a six figure salary to come on full-time with them. Early in the discussions, I brought up my podcast and newsletter, asking the publisher if I could continue operating them in my free time. We went back and forth on this topic for a few weeks before they came back with an official answer: no, I couldn’t continue with my newsletter and podcast.

They claimed that it had less to do with the medium than with the subject matter. They didn’t like the idea that I would be covering the media, particularly their direct competitors. But they never mentioned a ban on me tweeting about the media industry. The restrictions were specifically confined to my newsletter and podcast.

After giving it some thought, I decided not to budge. I had spent so much time and effort into building up an audience across these platforms, and I didn’t want to abandon that audience. We went back and forth a few more times attempting to hammer out a workaround, but eventually the negotiations trailed off.

In other words, I gave up some pretty good job security in order to continue delivering this newsletter to you. If only there were a way you could reward me for this sacrifice. Speaking of which…

This media company merged local news with content marketing

The last decade hasn’t been kind to local print newspapers. The rise of platforms like Craigslist, Facebook, and Google has devastated their advertising revenue streams. Private equity firms bought up entire newspaper chains and then bled them dry. Even those newspapers that haven’t shut down experienced massive layoffs and are often running on skeleton crews. This retrenchment resulted in the emergence of so-called “news deserts” -- regional information vacuums where no comprehensive news coverage exists.

As a journalist who covers the media industry, I’ve long been fascinated by the internet startups aimed at filling these vacuums. There’s TAPinto, a network of franchise sites that sprung up out of New Jersey. There’s 6AM City, a newsletter-centric company that operates primarily in South Carolina and North Carolina cities.

And then there’s The 100 Companies. Unlike most media companies that erect a firewall between editorial and advertising, The 100 Companies actually licenses its platform out to local PR and marketing firms. Yes, those firms can promote their own clients, but they’re also incentivized to curate quality local information that their subscribers will find relevant. I recently interviewed its founder Chris Schroder about how each site operates, what value it creates for PR firms, and why he’s expanding into other niches beyond local news.

To access this case study and others like it, you need to become a paying subscriber to this newsletter. By doing so, you’ll not only receive these case studies in your inbox, but you’ll also be supporting the production of the free newsletter and podcast. You get awesome content that’ll help you in your career and you’ll be supporting an independent creator. Subscribe at this link and get 10% off for the first year:

How the media industry’s relationship with Google search has changed

There was a time, before the modern rise of social media, when the entirety of a publisher’s audience development strategy focused on SEO. Media companies were obsessed with search engine traffic, to the point that they were crafting content that aimed to anticipate what people would type into Google. The Huffington Post headline “What time is the Super Bowl” is probably the most widely-cited example of this type of behavior.

Which is pretty ironic, since if you were to type in “What time is the Super Bowl” today, Google would present you the answer above the search engine results, meaning that very little traffic will go to any websites that publish this information.

You’ve probably noticed by now that a lot of Google searches these days return few clickable links, with huge chunks of text pulled from websites and placed directly below the search bar. Google’s gotten uncannily good at identifying which snippet of text from a much longer article best answers your questions. I didn’t realize how good until I read this Bloomberg piece about how much search traffic has been siphoned away from websites. This stat jumped out at me:

A turning point came in June 2019. That was when more than half of searches kept users on Google for the first time, rather than sending people to other sites through a free web link or an ad, according to data from digital marketing company Jumpshot.

A recent investigation by The Wall Street Journal focused on another aspect of Google search results: the video carousel. It also appears above standard search results, and a WSJ test found that YouTube videos are much more likely to be featured in this carousel, even in cases where identical versions of a video received more views on a different platform.

So what kind of damage is this inflicting on the media industry? Probably less than you’d think. Referral traffic is a lot more diversified today than it was a decade ago. Not only do you have myriad social media platforms to post to, but publishers have also doubled down on newsletters over the past few years.

The industry-wide pivot to paid subscriptions has also made Google search less relevant. Search engine visitors are notorious for bouncing off your website the moment they’ve gleaned the information they sought out. They’re not very likely to convert into paying subscribers or even result in a newsletter signup. Sure, you can serve that user a programmatic ad, but that will become even less lucrative as Apple and other platforms crack down on third party cookie data.

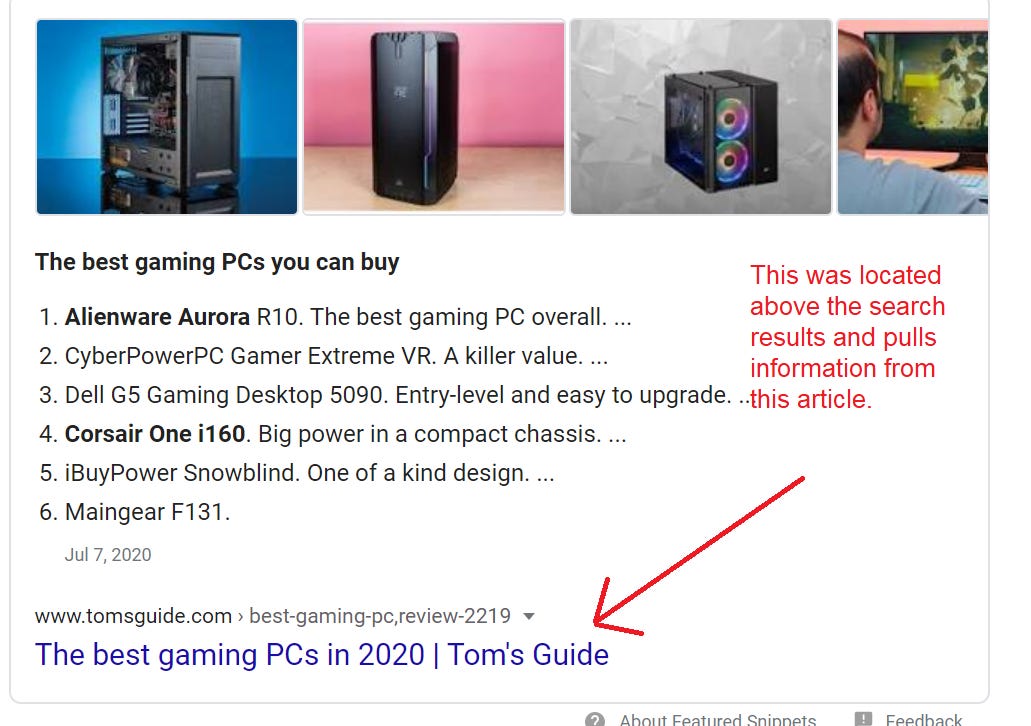

Publishers that rolled out ecommerce verticals in recent years might experience a more detrimental impact, since buying guides and product reviews are largely dependent on search traffic. For instance, I just did a search for “best gaming PCs,” and Google presented me with a list pulled from a buying guide website.

Sure, if you want detailed reviews of each product, you have to click through to the link, but a lot of users probably simply take the #1 ranked PC on the list and then plug it into Amazon -- which happens to have its own user reviews for one to peruse.

I’m not going to pretend to be an SEO expert, but given YouTube’s prominence above standard search results, my guess is that any search engine-focused strategy should involve an increased presence on the video platform. After all, YouTube does allow affiliate links.

Want to interact with me directly?

I have a secret Facebook group that’s only promoted to subscribers of this newsletter. I try to post exclusive commentary to it sometimes and have regular discussions with its members about the tech/media space. Go here to join. [link]

Other news

"The Atlantic wants a million people to 'attend' its festival this year, up from the 2,000 in-person attendees it normally attracts." [link]

Several publishers are experimenting with sending text messages to readers. It creates a deep level of intimacy. Obviously the interactivity part doesn't scale super well, but the journalist doesn't need to respond to every text. [link]

Apple is launching a daily news podcast. Is this Apple's first original podcast? Makes sense that it's integrated with Apple News. [link]

I continue to think that Jeff Bezos's longterm play with The Washington Post involves using it as an incubator for publishing/ad tech that can be scaled across the entire media industry. [link]

A few months ago I made a joke that I was starting a "Substack house" similar in function to TikTok houses. Looks like someone actually created one. Sort of. This article is frustratingly light on details on how this "house" functions. [link]

Do you like this newsletter?

Then you should subscribe here:

Simon Owens is a tech and media journalist living in Washington, DC. Follow him on Twitter, Facebook, or LinkedIn. Email him at simonowens@gmail.com. For a full bio, go here.

Creative Commons image via Pexels

"Because no matter how strong an outlet’s brand these days, no matter how sterling their reputation, more and more readers are simply following individual writers on Twitter, establishing singular bonds of trust that don’t necessarily translate to those writers’ outlets.

A revealing anecdote courtesy of Emily Bazelon, cohost of Slate’s 'Political Gabfest' podcast:

'This is something that’s happened to me a few times in the last, six months, nine months…

I’ll be talking with someone who is not political at all, does not follow news, I have no idea how they vote, and they’ll ask me what I’m working on. And I’ll start telling them about a story, and they’ll say, ‘Oh that’s really interesting, will you send that to me?’ or they’ll go find it and come back to me and want to talk to me about it.

And then they’ll say, ‘Can you send me the other things you’re writing? Because I don’t know what to trust. But now that I’ve met you, I want to read what you are writing.’

I guess it’s a compliment, but I also think it’s nuts!

The fact that you had a conversation with me somehow means that I deserve…it’s like we’re back in a town square where people are talking to each other personally because they don’t know who to trust, and because ‘Oh what’s coming in over my Facebook feed? I have no idea where any of it’s coming from,’ as opposed to ‘here are institutions.’

Sometimes I’ll try to gently say, ‘Well I work for the New York Times, and you could read other things from the New York Times,’ and I’ve had people back away from that idea, like, ‘Well, no, I don’t know what to trust in any particular mainstream media outlet, but I want to read you.’

I think it’s not a good sign.'

And not a good sign it may be.

But it’s also our current reality, and to not admit as much is to disrespect the truth we’ve claimed to so revere."

(http://worthwhiler.com/the-things-we-think-and-do-not-write-the-future-of-our-industry/)