Why most NFT owners are insufferable on social media

NFTs were supposed to be about supporting art, but in most cases, the art is beside the point.

Hello there! So this is the first edition of a new Q&A series where readers ask me questions and I do my best to answer them.

But there’s a catch: while the answers are free to read, only the paying subscribers are able to ask the questions. If you’re a paying subscriber who wants to ask a question for the next edition, you can leave it in this thread over here.

And if you want to subscribe, the link below will get you 10% off for your first year. Not only will you be able to participate in these Q&A sessions, but you’ll be supporting the work I do for my newsletter and podcast.

Ok, let’s jump into it…

Why most NFT owners are insufferable on social media

The first question comes from Jez Walters:

NFTs. Hype or a magnificent opportunity?

When I first started reading about NFTs, I thought they offered an interesting idea for how artists could monetize high quality digital content. Indeed, what triggered my initial interest was Beeple’s $69 million sale at Christie’s. I didn’t know who Beeple was at the time, but I’ve since become an admirer of his art, which takes modern pop culture and distorts it through a dystopian lens. NFTs seemed like a cool way to create scarcity around his art, which he released for free as a public good.

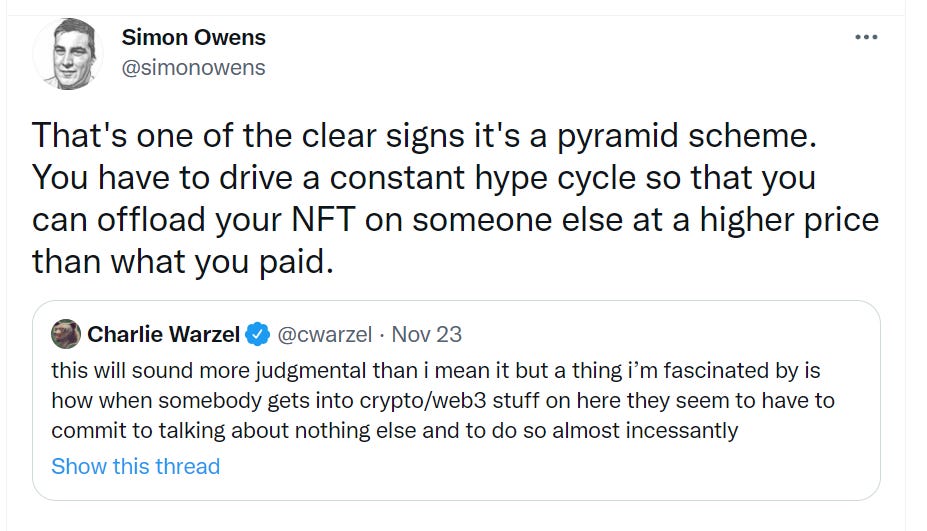

It didn’t take long for my views on NFTs to sour. As the entire crypto community turned its attention to the NFT market, it quickly became apparent that it had no interest in funding quality art; but rather, art was merely a vehicle through which crypto bros could create artificial scarcity that’s monetized through fanatical, evangelical hype. It’s basically Bitcoin cloaked in a bohemian narrative.

Take the Bored Ape Yacht Club, which is probably the most famous NFT project to date (outside of the Beeple sale). No one would argue that the titular apes are particularly well drawn; in fact, the art is beside the point. Instead, the creators are trying to monetize the scarcity of the apes by releasing them in limited batches, and when each person buys an ape NFT, they’re financially incentivized to start hyping the project nonstop with the aim of increasing demand. Each ape release then becomes another hype cycle, not only to drive up the prices of the already-existing apes, but also to generate financial interest in the next scheduled release.

This is why the social media accounts of NFT-buyers have become insufferable, and it doesn’t take you long to draw parallels to multi-level marketing companies (MLMs).

Anybody who’s had a friend or family member join an MLM knows what I’m talking about. They suddenly start posting about it 24/7 on social media. They talk about how their particular MLM is revolutionizing commerce and eliminating the 9-to-5 work structure that’s a vestige of the Old Economy. They enter into a cult-like camaraderie with their fellow MLM participants, attending live events together and tagging each other on social media. They also aggressively try to recruit new members into their MLM, since that’s the only way that they generate real revenue.

All the same dynamics apply to NFTs. If you buy an NFT for $1, then you want to drive up its price to $2 so you can make a profit. Not only that, but NFTs are written into the blockchain so that 10% of every sale is kicked up to its previous owners, so you’re incentivized to hype the NFT even after you no longer own it (MLMs have similar “pyramid-like” incentives). The only way you make money is by finding a bigger sucker who’s convinced that they can make even more money. There are very few end consumers who get into the NFT market because they receive any practical value from the NFTs themselves.

Crypto enthusiasts like to compare owning an NFT to buying a limited edition concert tshirt from your favorite band. But at least that tshirt has some tangible value. Not only is it a physical object that you can wear, but the band itself is presumably creating great art in the form of albums and live performances. Here’s a more apt analogy: Let’s say you put a computer on a stage and have it start spitting out random notes and chord progressions, none of which actually sound particularly good. And then you sell a limited edition tshirt for that performance. THAT is an NFT in a nutshell.

It’s been 12 years since the Blockchain was invented, and since then we’ve been treated to thousands of articles about how such-and-such startup was going to revolutionize a particular industry. Twelve years after the launches of Facebook, Google, and Amazon, it was clear that they had revolutionized their respective industries; how many Blockchain startups have achieved the same level of ubiquity? Outside of Bitcoin itself, most everyday people would struggle to name a single Blockchain product. So forgive me if I’m a tad skeptical of yet another wave of Blockchain technology hype.

What’s a good “non-core” skill for content creators?

A question from Fiona Mullen:

What is the one “non-core” content creator skill that has helped you the most, especially as a sole operator? (You can do 3 if it is hard to choose.) What do I mean? A lot of humanities grad solo content creators (like me) know how to research difficult topics, write good quality content, write fast, write a lot if required, write little if required, present things well. But that’s about it. I have few tech skills, no coding skills, no marketing know-how and no idea if (say) learning Python will change my life or be a waste of time. I am 55 but I even know 30-somethings with the same issue.

That’s an interesting question!

So my career has had a circuitous path. I started out as a newspaper reporter, then after two years got recruited by a DC marketing firm. Several years later I went back full-time into the journalism world, working as an assistant managing editor at US News & World Report. After that, I accepted a role at a PR firm, then spent several years as a freelance content marketing consultant.

I think my work in the PR/marketing world had two benefits:

It allowed me to better understand the direct connection between content and commerce. At my journalism jobs, I never once sat in on a meeting with the business team and only had a vague understanding of how they were monetizing the content created by the editorial team. While working in PR/marketing, I had direct communications with the clients; not only did I service them directly, but I also often played a role in the pitch and proposal-writing process. This gave me a lot of insights into how these companies measure success and how content serves their business goals.

These companies weren’t just hiring us to create content; we were also expected to help it spread online. This forced me to think strategically about how to build audiences and get them into a brand’s sales funnel. This became especially handy once I launched my own paid subscription business, i.e. this newsletter.

The last thing I’ll say is under absolutely no circumstances should you learn Python unless you actually think you’ll use it in your day-to-day life. The learn-to-code movement was always overhyped and I think most media professionals have basically concluded that simply memorizing a bunch of command prompts won’t actually provide any career value.

The debut of Creator Economy 2.0

From Sonya Mann:

What are you excited about right now, what has a bright future in your eyes? Either as an industry observer or as a participant. Ideally both.

I’m super excited for the emergence of what I call Creator Economy 2.0.

What is Creator Economy 2.0? It’s when creators and media operators team up to enable quicker and more sustainable scale.

Let me give you an example. In 2019, the editorial staff for Deadspin resigned en masse after repeated clashes with management. Under the Creator Economy 1.0 model, each staffer would have launched their own paid newsletter, and while the most prominent writers may have succeeded, most would have grown frustrated by slow growth.

Instead, the former Deadspin writers teamed up and formed a writer collective, thereby spreading out the burden of content creation, marketing, and monetization. By doing so, they were not only able to reduce burnout, but they built a sustainable business much faster than most of the individual writers could have on their own. At the end of their first year, they’d reached a run rate of $3.2 million and each staffer was pulling down a comfortable middle class income.

Each month, I see more and more of these Creator Economy 2.0 companies launching – from Every to Workweek to Puck.

But we’re also starting to witness its embrace from legacy media. The Atlantic is probably the most prominent example. It recently signed deals with several prominent writers; in essence, it’s offering up marketing, editing, and base salaries, and in exchange the writers receive a financial upside based on the number of paid conversions they drive. They also maintain a certain level of editorial independence.

Creator Economy 2.0 solves the “creator middle class problem.” As you probably already know if you follow the space, the vast majority of wealth is driven toward a relatively small percentage of creators. That’s because there’s a steep on-ramp that makes it extremely difficult to scale from $0 to a middle class income. Creator Economy 2.0 will allow creators to leverage many of the benefits of traditional media while also giving them some sort of equity in the business. That transfers wealth away from corporate media conglomerates and toward creators, which is something I find immensely exciting.

Did I not answer your question?

Don’t worry! This was just the first batch. I plan to continue answering questions in future editions. Make sure to leave me a question in this thread if you haven’t already.

And again, if you’re not yet a subscriber and want to join in on the fun, use the link below:

Quick hits

Pocket started as a read-later app, but now it's become a powerful content recommendation engine. It's able to leverage the data collected via its users' bookmarks to find and share high-quality content. [Adweek] From the article: “At Texas Monthly, for instance, Pocket readers spend 240% more time on the site compared to average readers, and return at a rate 17% higher than normal, said vp of innovation Brett Bowlin."

"If you’ve been reading about the metaverse recently, you’ll notice something is missing: a semi-cogent explanation of what it actually is." [Ed Zitron]

"Tyler has millions of fans but no friends; before spending a recent day with a Post reporter, no one besides his girlfriend and family had visited his house in several years." [WashPo] The life of successful Twitch streamers just seems so brutal.

Do you like this newsletter?

Then you should subscribe here:

Simon Owens is a tech and media journalist living in Washington, DC. Follow him on Twitter, Facebook, or LinkedIn. Email him at simonowens@gmail.com. For a full bio, go here.

"Not only that, but NFTs are written into the blockchain so that 10% of every sale is kicked up to its previous owners."

Is this accurate? I have never heard this before. I've read some discussions about royalties for artist-created NFTs (a % of each sale that goes only to the original creator, not previous owners.)

I generally agree with your take but if 10% of every NFT sale was going to kickbacks that would be truly insane.