Why Andrew Sullivan’s new paywall experiment will outlive his last one

His original blog required too much daily content. Substack will allow him to slow down and avoid burnout.

Welcome! I'm Simon Owens and this is my media newsletter. You can subscribe by clicking on this handy little button:

The year 2020 will be remembered for a lot of terrible things, but it also saw the creation of a market for independent internet writing, one that allows journalists and essayists to make a full-time living without the aid of traditional media companies.

Sure, bloggers like Ben Thompson and John Gruber proved long ago that such a career was possible, but it wasn’t until this year when writers, aided by the newsletter platform Substack, started quitting their salaried media jobs en masse to strike off on their own. Not a day goes by without an announcement on Twitter that a journalist is leaving their magazine or newspaper for Substack, and some of the biggest stars lock in six figure incomes within days of their debut on the platform. Since January, writers that include Matt Taibbi, Casey Newton, Glenn Greenwald, and Matt Yglesias have all cast off from their media motherships, taking their tens of thousands of readers along with them.

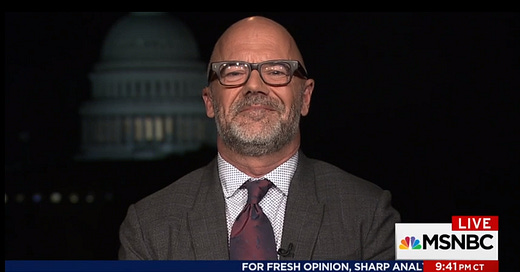

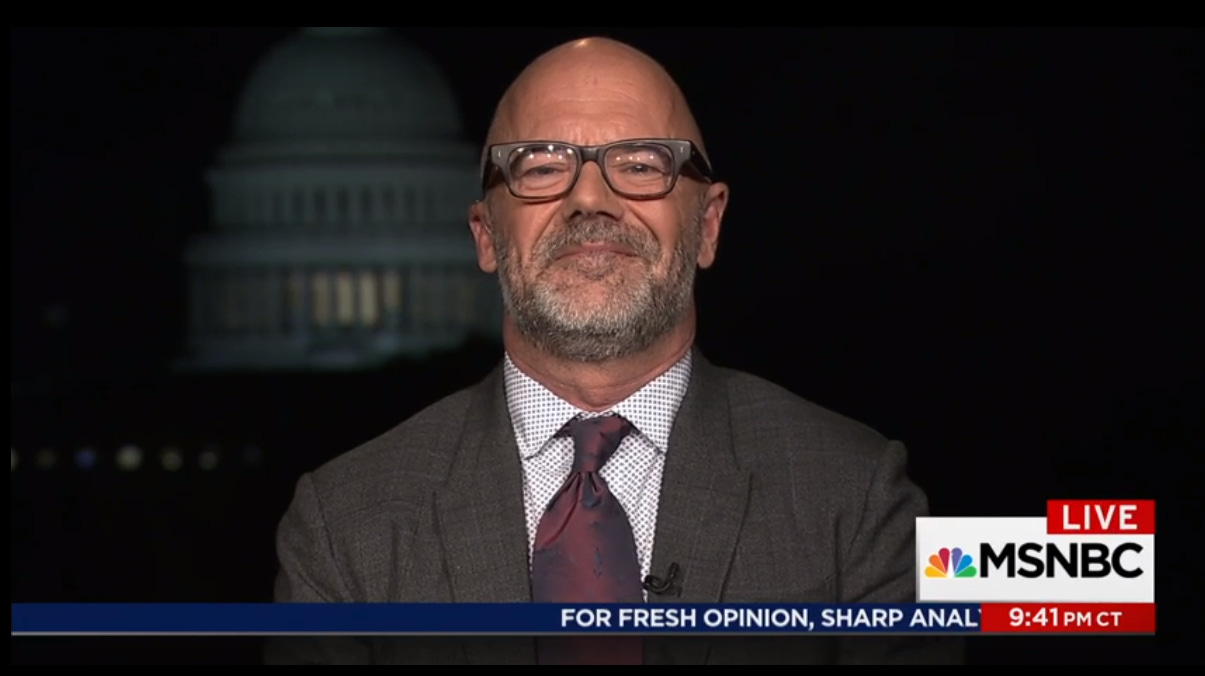

But of all the writers to launch on Substack this year, one stands out from the rest: Andrew Sullivan. In July, he announced that he and his editor at New York had mutually agreed that he would leave the magazine, which had been publishing his columns since 2016. In his farewell column, he acknowledged that his political opinions, particularly those that relate to race, had alienated much of the magazine’s staff and were “out of sync with the values of Vox Media.” He also included a link to his new Substack newsletter with the encouragement for his fans to sign up.

While much of the coverage of Sullivan’s move focused on his politics and whether he’d been “cancelled,” the more interesting question is why he chose to return to a format that he’d previously sworn off.

After all, this wasn’t Sullivan’s first rodeo; earlier this decade, in a period stretching from 2013 to 2015, he’d operated a standalone blog that was completely reader funded, and while outside observers had hailed it as a success for independent writing -- at its peak, it was generating over $1 million in annual revenue -- he abruptly closed it and swore off daily blogging. “I’ve had increasing health challenges these past few years,” he wrote in his announcement. “... My doctor tells me they’re simply a result of fifteen years of daily, hourly, always-on-deadline stress.” He was burnt out and ready to flee back to the warm comfort offered by traditional media. “I want to have an idea and let it slowly take shape, rather than be instantly blogged. I want to write long essays that can answer more deeply and subtly the many questions that the Dish years have presented to me. I want to write a book.”

So given his prior experience, why did Sullivan recently choose to return to the hellscape that is independent media? Is this a case of amnesia, or is it perhaps a proclivity for masochism?

I’m being slightly facetious, of course. The truth is that Sullivan’s return to solo writing is a complete departure from his original foray. Not only is the market for paid subscriptions much more mature than it was in 2013, but philosophies on internet writing and distribution have evolved since then, and as a result, Sullivan’s new model is sure to be much more successful, not only in terms of how much revenue it generates for him personally, but also in his effort to avoid burnout.

To understand why Sullivan struggled in his first independent venture, you first have to know a little about his history as a blogger. He launched The Daily Dish in 2000, years before the average person even knew what a blog was. A former editor at The New Republic, he got the idea for the blog while staring at a newsstand that sold UK print newspapers. “And I just realized that journalism has always produced material around the clock,” he recalled in an interview. “Why don’t I just start writing at different times and provide the readers with the kind of journalistic service that the London papers are doing?”

And he did blog around the clock, sometimes posting dozens of times a day. Most of these posts were short snippets of text with links, the kind you now find on Twitter. He amassed a huge audience and eventually moved his blog onto a series of mainstream news sites that included Time, The Atlantic, and The Daily Beast. With each successive move he brought with him an ever larger audience (at one point, Atlantic editors acknowledged Sullivan was responsible for at least a third of the magazine’s online traffic). By the time Tina Brown lured him to The Daily Beast, he not only commanded a huge salary, but also employed a small team of editors and interns who supported his brutal publishing schedule.

Given his large, loyal audience, Sullivan could have continued on that path indefinitely, but as his 2013 contract renewal approached, he began to long for something different. He’d grown to loathe the ad-driven ecosystem that, at the time, governed all internet media businesses, and he was encouraged by early paywall experiments that made publishers more accountable to their readers. "[W]e felt more and more that getting readers to pay a small amount for content was the only truly solid future for online journalism," he wrote. "And since the Dish has, from its beginnings, attempted to pioneer exactly such a solid future for web journalism, we also felt we almost had a duty to try and see if we could help break some new ground."

And so on January 27, 2013, Sullivan made the grand announcement of his new venture and included a link to where readers could enter their credit card information and sign up for his content. Within 24 hours of the announcement, he converted enough subscribers to generate $333,000 in annual revenue. A month later, it had a $611,000 annual run rate, and by the time he announced two years later that he would be shutting down the venture, he had 30,000 subscribers and $1 million in annual revenue. By all accounts, he was the most successful blogger in the history of the internet, at least up until that point.

But there were fundamental weaknesses to his model that ultimately led to the blog’s demise. The first was his price: just $19.99 a year, or $1.67 a month. That’s obscenely low, especially when you consider what he lost after credit card fees and the cut he gave to his paywall platform. That necessitated that he convert a huge portion of his daily readership into paying subscribers. To give you a sense of how low that price is, consider the fact that Substack won’t even allow you to charge readers less than $5 a month for a paid newsletter, and many of its most popular users charge $10 a month or more.

Why did Sullivan price it so low? Probably because he didn’t have much confidence that users would pay more. Remember, this was 2013. The New York Times’s paywall was only a few years old at that point, and there weren’t a lot of other examples back then of successful pay models, especially for blogs. He had no idea if people would pay to read the work of a single writer on the internet, and so he lowballed a readership that probably would have paid at least twice as much.

His biggest mistake, though, was in how he structured his paywall. Again, this was 2013. The publishing industry was only just beginning to experiment with paywall models, and most centered around some kind of meter that allowed for the consumption of several free articles before users were forced to pay up. And this was just the sort of model that Sullivan adopted for his blog.

Because a meter only succeeds when the same reader lands on multiple pieces of content, the model rewards publishers that generate a high volume of good content. For a newspaper like The New York Times, which employs over a thousand journalists, this is relatively easy to achieve. But for a small publisher built on the brand of a single writer? Sullivan essentially placed himself on a treadmill that was all-but-certain to lead to burnout.

This truth began to dawn on him within the first few months after he launched the site. The blog was set up so the homepage displayed a small snippet of each blog post in reverse chronological order, and to continue reading a longer piece, the user had to click a “read on” link, which would immediately expand to the full post. The meter measured how many times an individual user clicked the “read on” link, and it became clear pretty quickly that only a tiny percentage of his readership was clicking that link often enough to trigger the paywall.

A little over a month after Sullivan debuted the paywall, he noted that “only four thousand readers hit more than seven read-ons and were asked to pay. That’s only 0.4% of the total monthly unique visitors and 1.2% of the readers who hit at least one read on.” Part of the problem, he realized, was that a reader would consume the blog on multiple devices throughout the day -- mobile phone, home computer, and work computer. That made it extremely difficult for them to trigger the paywall. “We’ve decided to lower the meter to five free read-ons and extend the reset period from 30 days to 60 days,” he concluded.

But that wasn’t the only problem with the meter. Sullivan had a tendency to publish posts that simply provided a link to an outside news source with a block quote of what he considered the most relevant passage. If the block quote was long enough, it would be hidden behind the “read on” link. Now imagine if you were a reader who triggered the paywall while reading a blockquote from an outside news source Sullivan was curating. That’s probably the worst kind of content for converting a user from free to paid.

The meter also kept his overhead high. Because he had to churn out dozens of posts a day, Sullivan was forced to employ a staff of at least half a dozen writers and editors to help him with the output. That meant that, in addition to the constant pressure of posting around the clock, he also had the added stress of making payroll every month. He probably had to clear at least $600,000 a year before he could even begin taking home a salary.

And so, after two years of this, he threw in the towel. His announcement spawned hundreds of think pieces about the viability of solo blogging, including one from Ezra Klein, who opined that “blogging, for better or worse, is proving resistant to scale.” Because internet reading habits were fueled almost entirely by social media sharing, Klein believed that no single writer could achieve the output needed to generate a living. It was only by compiling the work of multiple writers that a publication could achieve the escape velocity it needed to survive.

Of course, we now know Klein was wrong in his assessment. Just ask his Vox co-founder Matt Yglesias, who now makes a tidy living publishing a handful of pieces a week on his Substack. Writing for his blog Stratechery, Ben Thompson took issue with Klein’s piece, arguing that “blogging has evolved. It is absolutely true that the old Sullivan-style — tens of posts a day, mostly excerpts and links, with regular essays in immediate response to ongoing news — is mostly over.” That style of blogging had been incorporated into platforms like Twitter and Facebook.

Thompson believed in an alternative model, one that relied “on quality over quantity” and trusted that readers would be willing to pay for value over volume. Thompson was speaking from experience, of course. After all, he invented the paid newsletter model that inspired Substack’s founders to create their company (fun fact: one of those founders, Hamish McKenzie, wrote an article for Pando in early 2013 expressing doubt that Sullivan’s model would work).

Which brings me to the present day and Andrew Sullivan’s new Substack newsletter. In so many ways, it’s the complete opposite of his Daily Dish blog. It costs $5 a month or $50 a year, meaning he can convert half the users to generate the same amount of money. Whereas the 2013 Sullivan published hundreds of posts every month, the 2020 Sullivan published just 14 in November. And while the old blog required a full staff to keep it running, his Substack appears to employ just one co-editor.

Most important of all, Sullivan now relies entirely on a decentralized form of distribution: email. He no longer needs to ensure readers are met with fresh content every time they reload the homepage, nor is he subject to the whims of the Facebook algorithm. He can hit ‘send’ on his latest missive and rest assured it’ll be waiting in the reader’s inbox the very next time they log in.

His Substack is everything his blog wasn’t, and yet...readers of The Daily Dish would still recognize the old blog in much of what Sullivan does. He still curates articles and block quotes them. He still posts views from his window. He still publishes emails from his readership. He still writes long essays. The only difference between then and now is that he packages this all in a single newsletter and then just sends it once or twice a week. Sullivan is able to work at his own pace, writing for a readership that probably wouldn’t mind or notice if he took a day or a week off.

People are often nostalgic and mourn the loss of the old blogosphere, but if Sullivan’s experience is any indication, the web we have now is much better. Blogging didn’t die; it evolved, and because of that evolution, talented writers are able to decouple their work from the mainstream media and follow their passions. Back in 2013, Sullivan sensed that this decoupling was possible; the problem, it turns out, is that he just needed the rest of the internet to catch up to his vision.

Do you like this newsletter?

Then you should subscribe here:

Simon Owens is a tech and media journalist living in Washington, DC. Follow him on Twitter, Facebook, or LinkedIn. Email him at simonowens@gmail.com. For a full bio, go here.

Here's what I thought while reading this piece (which is very well written and kept me engaged--top to bottom): You also could adopt many of the strategies that Sullivan employs and make it work for you on your Substack, Simon. As I went through your collection of posts this evening I thought, "I've seen a lot of this kind of content elsewhere." But who is this Simon guy? My suggestion: Personalize your Substack more. Take pictures out of your own window. Share some of the things that puzzle YOU personally about the topics you cover. How the hard parts were overcome. What it's like to be original (the nuts and bolts of it for YOU--not just what experts have written about it on Bloomberg Biz.

I've been 'blogging' since 1998, in fact, I was doing it when the word blogging didn't even exist--and what was it that built my audience and sustained my readership and the opening of wallets? I talked about myself a lot, but not in a solipsistic way.

People are still looking for the 'personable' online today -- now more than ever before as social media is proving to be a sort of vapid mirage of feigned contact.

So mix it up on your Substack. Don't be afraid to share and show things about yourself, especially if it steps out of the constant stream of success stories that have been done zillions of times before. You're also good looking and as my old friend always says to me: Your face is your fortune. Don't be afraid to mug more for the camera. People like looking at other good looking people.

I wish you success and congratulate you for where you are positioned presently--and will watch to see what's to come. I subscribed earlier this evening and will consider a paid subscription as we go.

Cheers,

Frederick

It’s interesting you comment that $20/year is “obscenely low” for the work of single writer. The likes of Sullivan and Greenwald have indeed shown that with sufficient clout it’s possible to hit a very healthy revenue number by charging more, but it remains to be seen if any more than a tiny percentage of the population at large think a price that’s ~ 50% of a Netflix or NYT subscription is good deal.