Was Randy Cassingham the first member of the Creator Economy?

In 1994, he launched This is True, one of the first email newsletters, and grew it into a thriving business.

Welcome! I'm Simon Owens and this is my media newsletter. You can subscribe by clicking on this handy little button:

Randy Cassingham’s coworkers didn’t believe anyone could make a living on the internet, much less from sending out emails.

One could hardly blame them. This was in 1994, back when most people barely even understood what the internet was. At the time, Cassingham was a technical publisher at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, and one morning he showed up to work excited about a new business idea that had sprung into his mind the night before: a free email newsletter. “They’re looking at me like I’m an idiot,” he told me. “They asked, ‘How can you make money by giving away this stuff for free?’”

Cassingham was undeterred, and he promised to return in a few days with a more formal business plan. “So I printed up several copies of my business plan and gave it to these people who were doubtful,” he said. “After they read it, they said this isn’t going to work, you’re not going to make any money. They assumed that because I gave it away for free, there was no income potential, even though I said in the business plan that I could publish books, I could syndicate this to newspapers, I could sell advertising. They just didn’t see it.” The document even projected how long it would take for him to generate a full-time income: two years.

Soon afterward, he launched This is True, a weekly email roundup of weird and quirky news stories. And two years later, almost to the day, Cassingham quit his job and moved to Colorado. By that point, This is True had tens of thousands of readers, had sold thousands of books, and was syndicated to newspapers all across the globe. Cassingham had been featured in outlets like The New York Times, LA Times, and Newsweek, all of which wanted to explain to their readers what the internet was and what people could do on it.

Flash forward almost 30 years, and it’s no longer considered crazy to think a creative person could generate a living on the internet. Hundreds of thousands of people who work in what is often referred to as the Creator Economy collectively take home billions of dollars every year. And though it’s impossible to definitively pinpoint the first creator to crawl out of the internet’s primordial ooze, Cassingham is certainly a contender.

Why did Cassingham think he could build such a business, especially when many of the basic tools of internet commerce didn’t even exist yet? He had to figure it all out himself, and in the process he helped influence innovations in modern email marketing. He walked me through his journey in a recent conversation.

Let’s jump into my findings…

It all started with a corkboard

Today if you want to launch a newsletter, you use one of the hundreds of email service providers that range from Mailchimp to Substack. But in the early 90s, there were no ESPs; in fact, it was still difficult to send messages outside of your own organization.

Working at NASA, Cassingham had access to cutting edge email products, but his interest went well beyond his dayjob. He recalled walking into a book store in 1993 and buying The Whole Internet User's Guide and Catalog, by Ed Krol; it was the only book in the entire store about the internet. “Literally the first thing I did when I got a network connection on the job — and I already had this book in hand — was that I asked myself, ‘what is the farthest thing I could connect to?’” It ended up being a server in Australia. “I followed the directions. I typed the command, and a second and a half later, I got the prompt, ‘yes, how can I help you?’ And I was like, woah.”

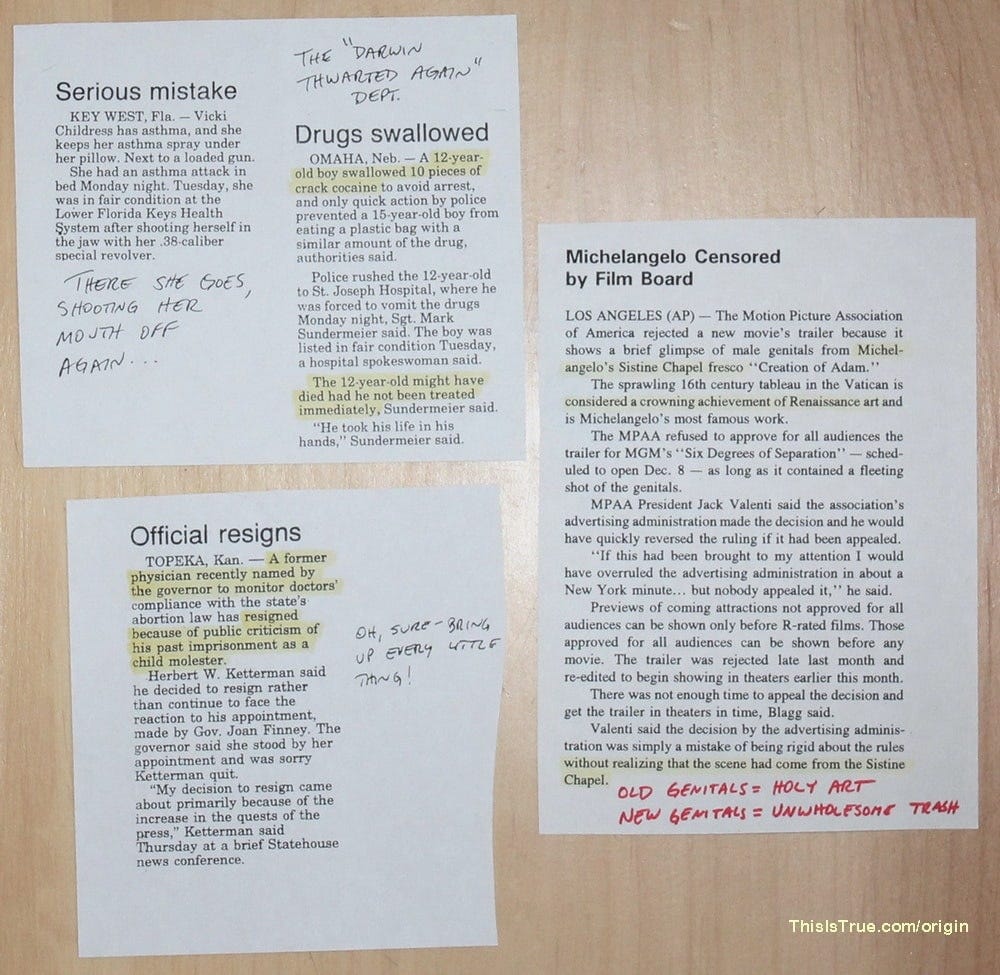

The idea for This is True came not from reading other email newsletters — Cassingham maintains he wasn’t subscribed to any at the time — but from a corkboard he kept outside his office. “I would clip out news articles, highlight parts of them, hand write little comments on them, and stick it on the bulletin board,” he said. “And anytime I put up new news clips, people would gather at my bulletin board in the hallways, and they just loved this stuff.” A clipping from 1991, for instance, is about a woman who kept both her asthma inhaler and gun under her pillow, an unfortunate pairing that put her in the hospital with a bullet to the jaw. Cassingham’s commentary is written underneath it: “There she goes, shooting her mouth off again…”

Cassingham had been posting to this board since 1987, but it would take seven years or so before it would collide with his newfound obsession with email. In June 1994, LA was hit by a particularly bad heatwave, and one night his inadequate air conditioning left him awake and struggling to fall asleep. “My mind kind of churned, and then suddenly this idea dropped into my consciousness, fully formed.” At the time, most people who had email addresses used them to forward jokes, and what were his bulletin posts other than topical, news-driven jokes? His idea that night was relatively simple: he would take the basic structure of his corkboard clippings and convert it into a newsletter.

By the time Cassingham fell asleep that night, he had not only settled on a format for the newsletter, but also the business model. And despite the skepticism he received from his coworkers the next day, he immediately set about launching it.

He still had to navigate the technical hurdles, however. Remember, there was no Mailchimp back then. Cassingham needed a way to compile a large list of email addresses and distribute to them all at once. Luckily, the Ed Krol book he’d bought mentioned a service called Majordomo, an early mailing list manager that would provide most of the functionality he needed.

A few days later, Cassingham sent an email to all of his personal contacts. “It said, ‘hey, I’m starting this newsletter. Here’s the first issue. If this is something you like, here are the instructions on how to subscribe.’” There was no landing page where people could sign up; instead, you had to send an esoteric command prompt to a Majordomo address. “Immediately, I started getting subscriptions. The first one was my best friend from high school.”

The newsletter version was slightly different from what Cassingham posted to the office corkboard. After all, those articles were protected by copyright, so he couldn’t simply reprint them in full. Instead, he rewrote the stories in his own words, which made it much easier to quickly get to the point and set up a punchline. Each item ended with his pithy commentary, which often involved some sort of pun-based joke. The email was a couple hundred words, all painstakingly composed by Cassingham, but perhaps the most important line appeared at the very bottom. “When I sent out the first issue, I said that if you know anybody you think would like this, go ahead and forward it. It did have a copyright notice on it, but it said you’re welcome to forward it as long as you do it in its entirety.”

Back in 1994, the term “going viral” hadn’t been invented yet, at least in terms of spreading internet content, but that’s the phrase we would use today to describe what happened with This is True. Within days, the newsletter had spread well beyond his own circle of friends. “I remember getting a subscription from someone in Singapore and thinking, ‘I don’t know anybody in Singapore,’” he said.

Cassingham’s list grew so quickly that it soon threw up logistical hurdles. For example, Majordomo only allowed for lists of 10,000 email addresses; anything larger than that and it started to suffer from delivery issues. Cassingham was forced to begin creating separate lists and then sending the newsletter out in batches. And because he stored the lists offline, that meant he had to manually remove addresses that unsubscribed or bounced back; this quickly became a logistical nightmare that ate up more and more of his time.

While This is True initially relied on word-of-mouth, it soon got a boost from the legacy media. “Journalists had to cover this new thing called the internet,” Cassingham said. “And the obvious question for them to answer was: what can you do there?” The primary use case for the internet at the time was email, and given that Cassingham was running one of the first newsletters, he was a natural interview subject. “Because my newsletter was journalism based, journalists loved it. They would use it as an example for their lay audience of what you can do online.”

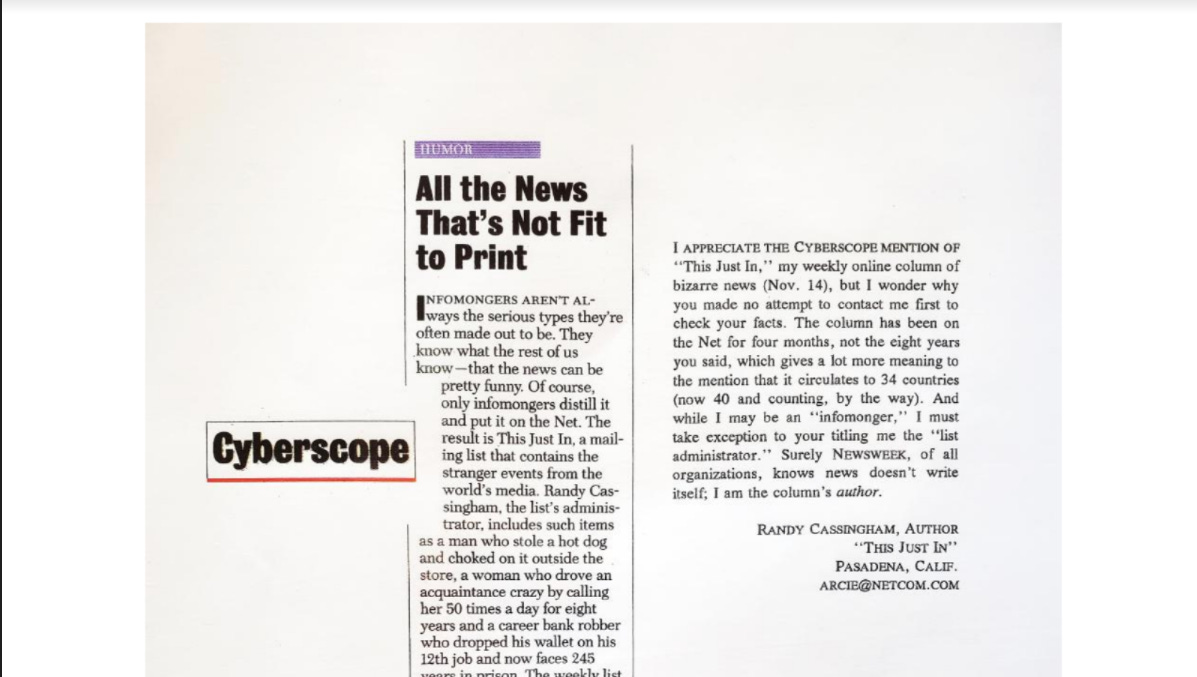

Cassingham still remembers the day he received a call from a fact-checker at Newsweek; the magazine was running a several-page spread of items that could be found on the internet. He was also the subject of longer profiles in The New York Times and LA Times. “How did he get so popular so fast?” wrote the NYT tech columnist. “Well, for one thing, he writes funny stuff.” Every time such an outlet featured him, he’d see a wave of new signups. It was a testament to the reach these publications had that they could drive so much attention even though a very small portion of their audiences even had access to the internet.

One thing nagged at me as I spoke to Cassingham: where did he source his news stories? This was before newspapers had websites, remember, meaning that they were mostly limited to regional distribution. Even when you allow for the fact that Los Angeles probably had a healthier newspaper industry back then, surely there wasn’t much space in the print broadsheets for the kind of oddball stories the newsletter featured. “I figured out how I could subscribe to and quickly skim through the AP, UPI, and Reuters newswires,” he explained. “It was a dial up thing I could do that wasn’t available on the internet proper.” Cassingham paid for these services by the minute, so he learned to quickly log in, scan the feeds for interesting headlines, download them, and then log out.

Monetization

By the end of the first year, Cassingham had a monster email list, and thousands of new signups were pouring in each month. This is True had succeeded wildly beyond his own expectations, and he soon decided it was time to move forward with monetization.

His first business model was fairly simple, at least on the surface; he would compile the entire year’s worth of newsletters into a book. Today, such a project would be relatively easy to accomplish, in that you could have a book up in the Kindle marketplace in a few hours and even sell a print-on-demand version. But in 1995, ecommerce barely existed; Amazon was only a year old, and Cassingham sure as hell didn’t have the connections to get his foot in the door at the major New York publishers.

So Cassingham went the self-publishing route, one that involved finding a local printer that could print him copies in bulk. The larger the print run, the less he paid per copy, so he tried to calculate how many books he could print to make it possible to generate a healthy profit margin but still have room to store them in his garage. “What I came up with was 3,000, because that would get the cost down to about a dollar per copy.”

Next, Cassingham began promoting the book within the newsletter. “I basically said send a check for X dollars to this PO Box,” he said. Orders immediately came trickling in, and he set aside time every week to send out round after round of shipments. To cut down on costs, he simply wrapped each copy in clear, air-sealed plastic. “I would print a mailing label and invoice with a piece of paper, fold it in half, and slip it in with the book.” This made it easy for the carrier to see the mailing address, and if you flipped it over you could see the cover of the book.

Demand for the book was strong, and Cassingham was surprised when people purchased multiple copies. “Once people read it, they often bought another one,” he said. “They’d let a friend or a nephew read it. Kids loved these books.” By the end of the first year, he’d sold all 3,000 books. Given that he was netting $10 for every copy, that meant he generated $30,000 in profit from a single printing.

Another early monetization goal was to get This is True syndicated in newspapers. This was an era when newspapers were inundated with print advertising demand, which required that they stuff their pages with more copy just so they could expand their inventory. To meet this demand, they often syndicated content, and some top columnists and cartoonists generated millions of dollars a year. Creators Syndicate was the biggest distributor of such columns, and the agency offered Cassingham a contract during his second year of writing the newsletter. “I was gleeful because it validated what I was doing,” he said. “But I knew in syndication you split all the income 50/50 with the syndicator. I was like, no, I don’t want to give a percentage like that. I turned them down. It felt very scary.”

So Cassingham began pitching newspapers directly about syndicating This is True, and at its peak it was appearing in outlets spanning across four countries. At some point, he became so bogged down by the technical issues of sending the newsletter — every edition was triggering thousands of email bounces — that he reduced its frequency to every other week. On the weeks that This is True didn’t get sent as a newsletter, a version of it still went out to Cassingham’s newspaper clients.

One day in 1995, Cassingham received an email from a reader who wanted to advertise in This is True. The ad would be for an early internet-based direct marketing company called Yoyodyne, which ran regular contests that people could enter to win a car, and in exchange they gave up their email addresses and other personal information. The reader who emailed Cassingham was none other than famed internet marketer Seth Godin. Advertising soon became a regular fixture in the newsletter.

By 1996, Cassingham had a steady mix of book, advertising, and newspaper syndication revenue, and he was quickly approaching the two-year anniversary of the newsletter’s launch. Remember, his original business plan had called for a two-year horizon for it to generate a full-time income, and he had long dreamed of moving from LA to Colorado. “Everything I made that wasn’t soaked up by food and rent was going into the bank,” he said. “So at the end of two years, I had a nice chunk of money saved.” By his calculations, he had enough to live on for at least two years, even if he received no additional income “So I pulled the plug, quit my job, and moved to Colorado.”

A year later, his income remained steady, and he still had the exact same amount of money saved. “And then the apartment I was living in informed me that they were raising the rent, and I was like, oh shit, that’s throwing a monkey wrench in my plans.” Cassingham ended up buying a townhouse, which required that he take all of his savings and put them into a down payment. Very suddenly, his financial situation didn’t seem so secure.

Cassingham’s business model also began to stall out. His book publishing operation was difficult to scale, and newspaper syndication was always a small portion of his revenue mix. He also didn’t have the time or inclination to hunt down new advertisers. By that point, he had over 150,000 subscribers to This is True, and he needed a way to more directly monetize that audience.

He eventually decided to launch a paid version of This is True. I know I’m starting to sound like a broken record at this point, but back in 1997, there was no existing infrastructure to make that transition simple. Today, it takes just a few minutes to connect a Substack newsletter to a Stripe account, and voila, you have a paid newsletter.

Back then, it was difficult for your average person to even take in payments via the web. “Just finding somebody with a website that had a security certificate was a big deal,” said Cassingham. “One of my readers said they’d host a little online shopping cart for me. There was no online processing at that time, so I’d get the order with the address, the total amount of their payment, and their credit card information. I would literally type in their credit cards into software that would then dial up the payment processor.” This was an entirely manual process that ate up a significant portion of Cassingham’s work week, at least until online payment software became more widely available. “I didn’t have a Paypal account until sometime during the year 2000.”

In January 1997, Cassingham announced the paid version of This is True. Free subscribers would still receive each edition, but those who paid $15 a year got an expanded version that included additional stories. “I launched the paid version in January, and by March I had 726 paying subscribers.” Within two months, he was generating an additional $11,000 in annual revenue, and the subscription base was steadily growing. “I knew at that point I’d be able to make it.”

The newsletter enters the Web 2.0 era

If there’s a recurrent theme to Cassingham’s newsletter career in the 90s, it’s that the early web was an inhospitable place for solo content creators. What online businesses did exist were custom built at enormous expense, and there simply weren’t many low-cost services aimed at helping small publishers distribute or monetize content.

The dawn of Web 2.0 changed all of that. The early 2000s saw the launch of thousands of startups that focused on removing nearly all of the technical friction that came with publishing to the open web.

This came as a huge relief to Cassingham, who by the late 90s was buckling under the strain of sending out This is True. His list was several years old, and thousands of the email addresses had been abandoned and were triggering bounce backs. “Mostly I could see what address was bouncing and delete them from the list, but this became incredibly tedious as the list grew.”

His first big break came when he struck up an online correspondence with a reader of his who worked in a government research lab. “He ended up doing some consulting work for the first email service provider, which was called Lyris,” recalled Cassingham. “He knew that they were just about ready to launch. They had the software built.” The friend offered to connect Cassingham to Lyris’s founder, John Buckman, who was on the lookout for a large email list so he could test out his software.

When Buckman got on the phone with Cassingham, he quickly inquired about the size of his newsletter’s email list. “I told him it was a little short of 150,000 email addresses,” he said. “I was met with a few moments of complete silence, and then he was like, ‘ok, I’m going to have to buy more hardware before I can do a list that big.’”

In 1997, Cassingham moved his entire list to Lyris, and the change almost immediately freed up hours of his work week that had been dedicated to manual tasks. For instance, Lyris automated the process of removing bounced email addresses from the list, which reduced the bounces landing in his inbox to a trickle.

Over the next few years, Lyris continued to launch new tools that made Cassingham’s job easier. While its early automation of unsubscribing inactive users was highly effective, plenty of bounces were still making their way to Cassingham’s inbox. That’s because the person who initially signed up for the newsletter had since moved on to other email addresses, making sure to automatically forward all correspondence to the new address. But when that new email address was subsequently abandoned, then it became impossible to trace the bounce back to the original address.

For instance, if the address A[@]xyc.com automatically forwarded to B[@]xyz.com, and then B[@]xyz.com became defunct, thereby triggering bounces, then there was no way for Cassingham to know that he needed to remove the A[@]xyc.com email address from his list. “Lyris eventually got to the point of having specific addresses for each subscriber, so when it eventually bounced back, it didn’t matter where the bounce came from, because it was coded to the original address.” This basically presaged the invention of sophisticated marketing segmentation that allows email service providers to target specific users based on whether they opened or clicked within an email.

Lyris was, in many ways, a revolutionary product, in that Buckman correctly predicted that millions of companies would one day facilitate most of their online marketing and communication through email. “He ended up with a really good product, it did really well, and he eventually sold it for millions of dollars,” said Cassingham. Many of Lyris’s early features were based on requests he had made for This is True. “Basically what it meant was that I was defining best practices in the email newsletter business.”

After Buckman sold Lyris, Cassingham started looking for a new email service provider and eventually landed on a product called AWeber. There was only one problem; by that point the This is True email list was 15 years old, and with spam filters becoming more aggressive, AWeber’s CEO didn’t want the risk associated with migrating so many defunct email addresses over to his service.

This led to Cassingham making a pretty radical decision: he would launch and grow a new list from scratch. For a period of several months, he included a message within each newsletter. “It said, ‘I’m moving, and you have to resubscribe. I’m not going to just import everybody’s email address over to the new list.’” By the time he relaunched the newsletter on AWeber’s platform in 2010, the list had been cut in half. “But the reality is those people weren’t there,” he explained. “They were either not getting anything because they were one of the people who changed their address multiple times, and the forward chain eventually broke, and so I was sending newsletters into the ether, or they were getting it and not opening it.” While losing half his list triggered a blow to his ego, it didn’t take long for Cassingham to see the silver lining. “My sending bill was cut in half.”

The dawn of the Creator Economy

Two decades after Cassingham launched This is True, the Creator Economy finally caught up to him. In the early 2010s, paid newsletters like Stratechery and Hot Pod began to attract attention, and then the debut of Substack led to a veritable explosion of the paid model. Hardly a week goes by without a star journalist decamping from a legacy publisher to launch their own newsletter business.

Cassingham has no desire to migrate to a Substack-like platform — he doesn’t want to hand over a percentage of his earnings — but he’s glad to see so many people embracing paid newsletters. “I think it’s terrific,” he said. “I don’t consider them competition, in that they're doing their thing, and I’m doing my thing. There’s very little overlap.” In fact, he thinks his own business is benefiting from the trend. “They’re establishing that good writing is worth paying for. It helps consumers understand that there’s a cost to getting something free.”

Today, Cassingham still lives in Colorado, and he enjoys the life of being an independent creator. “I work every day, seven days a week, but I also play every day,” he said. “If a friend wants to go out to lunch, then sure, I can take several hours off.” Looking back, it’s kind of amazing to consider that so much of his innovation can be traced to a simple cork board and a hobby for posting newspaper clippings. Back in 1994, his coworkers scoffed at his newsletter idea, but Cassingham was merely 20 years early to a business model that would transform the entire content industry. He may or may not be the first member of the Creator Economy, but he certainly gets credit for forging a career path that hardly anyone else — even the internet’s most enthusiastic visionaries — thought possible.

Do you like this newsletter?

Then you should subscribe here:

Simon Owens is a tech and media journalist living in Washington, DC. Follow him on Twitter, Facebook, or LinkedIn. Email him at simonowens@gmail.com. For a full bio, go here.

Fun read, thanks Simon. One complaint: I've been a subscriber to Randy's list for so long that I had a vague recollection of the fact that This is True was NOT the original name of the newsletter. I kept waiting for that part of the story, if for no other reason than to be reminded what it was. I understand you deciding not to spend a bunch of words detailing the switch from This Just In to This is True, but it's clearly part of the interesting history of Randy's pioneering publication. As a journalist, you should have mentioned it 🤗

I don’t wanna be too much of a niggler. 3,000 books sold for net $10 would’ve meant a $20 book. A 32-page newsletter cost us $1.00 a copy to print and 70 cents to mail when Randy was starting up. A book would cost a lot more. Great model if you’ve got $15,000 in cash to risk. The printer gets paid first. It’s a great peek at how print readers jump started online audiences. Thanks for taking us small publishers down the memory lane of the 90s, though. Love your newsletter!